Systems of Harm: 3 principles for creating socially responsible design systems

_This post is based on a talk I gave at this year's Smashing Conf in Freiburg, I'll add a link to the talk once it's available.

When we talk about the benefits of design systems, we tend to repeat 3 promises.

- efficiency: a design system will reduce waste in your design and development processes, and help you go faster

- consistency: a design system will help you standardise your digital experiences

- scale: a design system will help you scale your design decisions across your product landscape

But here’s the thing we rarely ever say: None of this is inherently valuable.

Now you might be wondering why I, a design systems consultant, am saying this. But the important bit is this word inherent. It doesn’t mean these things can’t be massively beneficial, but it’s worth being clear that:

- efficiency is only valuable, if it helps us move faster towards meaningful outcomes for the people using our products and services

- consistency is only valuable if we standardise things to a good level of quality. There’s nothing good about consistently crap

- scaling things is only valuable if they’re actually worth reproducing

And although this might sound obvious, I say it because I’ve noticed a shift in the conversation around design systems lately that concerns me.

If we agree that there’s no inherent value in the added capability promised by design systems - efficiency, consistency, and the ability to scale - then the value must lie in what we do with it.

But this introduces a problem. Because if we can use our design systems to speed up meaningful work, standardise things to a high quality, and scale the things we actually want to reproduce - then the reverse is also true.

It means that we can also use our design systems to speed up problematic work, standardise things to a poor quality, and scale things we don’t want to reproduce.

In other words, not only is this work not inherently valuable, it’s also not inherently harmless.

Design systems are scaling machines

To understand how design systems present a risk, let’s look at how they work, at the most basic level.

We create design systems by curating and distributing a collection of components, patterns and content. And as product teams start using the system to build websites and applications, things start to get scaled across our digital landscapes and even beyond, as they start to influence offline channels. But it’s important to say again that the mechanisms our design systems use to scale have no inherent value unless they’re things we actually want to scale.

And what if they’re not?

What happens if those components are inaccessible?

What of those patterns we’ve created are discriminatory?

And what if the content we’ve documented and disseminated is exclusionary?

What happens, in these situations, is we create a system of harm.

We industrialise discrimination and set up a production line which allows us to ship exclusion to the people using our products: quickly, consistently, and at scale.

So a few months ago I decided to make a podcast about this.

Systems of harm: the podcast

I wanted to explore the ways in which design systems can perpetuate harm, and how we can mitigate that. The podcast is called Systems of harm, and if you’ll indulge me in a shameless plug - it’s available now on all the usual podcasting platforms.

Throughout the series, I spoke to 6 amazing guests, who I’ll introduce you to as we go through this post. I deliberately sought out people who knew about design systems, but who also had personal experience of marginalisation and discrimination.

And what I really wanted to understand by talking to all of them was, if design systems can become these vectors for harm, then what can we do to mitigate that?

Through those conversations, I identified 3 principles. They are:

- To start with the teams who make design systems

- To centre stress cases

- To embrace complexity

1. Start with the teams who make design systems

Starting with the teams who make design systems.

Of all of the micro and macro decisions we make when instating design systems, the makeup of the team we hire to set up and maintain them seems to be the area that gets least attention.

We seem to assume that if individuals have the right practical skills and experience then we should unquestioningly hire them.

But that means that we’re often not thinking consciously about the perspectives and the biases that we feed into our design systems.

Let’s consider bias.

Every one of us makes thousands of big and small decisions every day.

Even as I’m writing now I’m making decisions about how to punctuate this post, when to take a sip of my tea, how to sit comfortably, and so on.

If I thought consciously about every one of those decisions I wouldn’t be able to function.

So to cope with that, our brains make unconscious decisions on autopilot, based on what they’ve learned from our past experiences.

And these unconscious decisions are our cognitive bias.

In the first episode of Systems of Harm I spoke to David Dylan Thomas, who if you don’t know him, has literally written a book on this subject of cognitive bias.

David explains that we are not going to be able to switch off this autopilot, and nor should we try to because we would just become completely inefficient.

He says that what we have to do instead is ask ourselves which of these biases that we have are harmful, and what are we going to do to counteract them and mitigate against the harm they might cause?

And one way we can do this is by counterbalancing them with other perspectives.

But this is challenging right now because, if you hadn’t noticed, the tech industry has a diversity problem.

Our society and therefore our organisations - even the more inclusive ones - are rife with inequality.

It’s why we have a persistent gender pay gap. It’s why diversity within our industry continues to be seriously lacking.

It’s why in my one design system team, as a woman, I was outnumbered 4 times over by white men called Matt. Now it’s really important to say that diversity isn’t inclusivity.

Diversity is just variety, and aiming to recruit a diverse team without thinking about inclusivity is a recipe for disaster.

But if we don’t have or can’t sustain a diverse team, it’s a good indicator that it’s not inclusive.

And this becomes a self-perpetuating problem because it informs our biases about what tech teams should look like.

David talked about this when I spoke to him. He said, when I say “web developer” you picture a skinny white guy. It’s not because you think people who aren’t skinny white guys can’t be developers, it’s just pattern recognition. But when it’s unconscious, it becomes dangerous to hiring practices.

When the teams who create and maintain our design systems are biased towards a narrow set of experiences, that bias propagates throughout all the layers of the people who interact with it.

It impacts contributors, people who use the design systems to make products and services, the people who work in our wider organisation, and the people who use the products and services our design systems are used to create.

The knowledge and experiences that we feed into our design systems travel down through these layers and start reinforcing those biases out in the world.

Now you might be thinking “can’t we just do user research with a representative group of people?”.

But without having diverse teams building our products, issues will slip through the cracks,

You can’t simply retrofit inclusion into your product. A lack of inclusion is not a bug that can be fixed in QA.

User research can help us to spot some issues, but by then we’ve already fed the system with so much of our own biases that it’s going to be unrealistic to make fundamental changes to what we’ve designed.

It’s really important that we address bias at the source by making sure that the team who’s building the design system can do so with different kinds of knowledge.

And I like to think of a concept here that I heard about from Kim Crayton, an Anti-racist Economist who does a lot of anti-racism work and education.

She talks about 2 types of knowledge:

- Explicit knowledge - the kind of knowledge that’s easy to articulate, codify and store, and can easily be transferred to another person

- Tacit knowledge - knowledge developed through a person’s lived experience, and is difficult to transfer to another person by writing it down and verbalising it

It’s this second kind of knowledge that allows us to really propagate our own experiences of biases through our design systems - and this is what determines the inclusivity of our products.

A strong example of this is from my guest in episode 4 of Systems of Harm, a design systems designer and now manager, Fred Warburton.

A few years ago, Fred was diagnosed at a young age with a degenerative eye condition called retinitis pigmentosa, and he was told he was losing his sight.

I worked with Fred at Babylon Health, and in that time I watched him lead one of the most incredible pieces of organisation-wide accessibility advocacy and education work I’ve ever seen.

In his episode, Fred and I talked about the impact of having a disabled person leading this work.

He said “My situation made it more tangible for people. Because it’s far more difficult to relate to some of this accessibility advocacy stuff if you don’t have an inclusive workforce that includes disabled people.”

I had a similar conversation with Imran Afzal in episode 5, principal designer on the design system team at co-op digital.

Imran and I talked about design systems and racism, and the impact of having all-white teams designing products and services.

He told me about a study in 2020 that found that 5 out of 6 leading speech recognition systems were better at recognising white people than people of any other ethnic background.

I’m going to assume that no one working on that software set out to exclude anyone, but this is just what happens when a team that isn’t diverse builds systems.

And this doesn’t just impact the people who end up using our products. It also affects people in the team itself.

What really struck me from talking to Imran is the amount of mental capacity he has to dedicate to thinking about what it means for him to be the only person of colour in an otherwise all-white design systems team.

He said that at some point he came to this realisation that he was the only person of colour in his team - in many teams he’s worked in - and that the effect of this builds up over time. He feels like he has to work harder than his white colleagues to prove himself and to win people over.

Imagine if he was free to just put that energy into his work?

If we’re not building our design system in an inclusive environment that supports participation from a diverse set of perspectives - we can’t design inclusive experiences.

And if we haven’t experienced exclusion, it’s very hard to mitigate it because we’re much less likely to spot it until it’s too late.

I am not a diversity, equity and inclusion expert and I’m not going to pretend to be, but I can see the impact.

I can see the correlation between the attention paid to inclusion in teams and organisations and the inclusivity of the experiences they create.

2. Centre stress cases

The term ‘stress cases’ was coined by Eric Meyer and Sara Wachter-Boettcher in their book Design for Real Life, which I really recommend if you haven’t read it.

The book says: “Real life is complicated […]. We might experience harassment or abuse, lose a loved one, become chronically ill, get into an accident, have a financial emergency, or simply be vulnerable for not fitting into society’s expectations.”

Historically, our industry has called these edge cases because they only affect a small number of users.

In the book, Sara and Eric propose redefining these situations not as edge cases, but as stress cases: the moments that put our design and content choices to the test of real life.

Instead of treating stressful situations as fringe concerns, we should move them to the centre and start with the most vulnerable people, and then work our way outwards.

Let’s look at a specific example of this. It comes from one of the book’s co-author, Eric.

A few years ago Facebook launched a feature called ‘your year in review’.

It showed the user the most important moment of their year - defined as whichever photo they’d got the most engagement on.

The photos were accompanied by colourful graphics and tonally celebratory content.

This feature was designed with a single context in mind: The person whose most liked photo was of a happy memory. But unfortunately, the feature made headlines for all the wrong reasons.

Facebook received multiple complaints from users who experienced the feature as something much more painful, and much more complex.

One of these people was Eric.

Eric’s daughter had died earlier that year, and he’d shared the news on the social media platform.

For pretty obvious reasons, the post had received a lot of comments and engagement, and therefore it shot straight into the top moment of his year in review.

Eric said, heartbreakingly, “yes - my year looked like that, true enough. My year looked like the now-absent face of my little girl.”

While I’m sure that lots of people probably enjoyed the feature, we should ask ourselves whether that enjoyment is worth the pain of those who experienced it like this. (It’s not.) This is why centering stress cases is important.

Another example of why this matters comes from my guests on episode 3 of Systems of Harm, Laura Parker.

Laura is a UX writing and content design consultant, and she struggles with a condition called Dyscalculia.

Dyscalculia is a learning difference that affects an estimated one in twenty adults in the UK. It’s characterised by a persistent difficulty with understanding numbers.

Laura talked about how it affects her everyday life.

We can help people with low numeracy and dyscalculia by providing alternative formats to information presented as numbers, tables and graphs.

Laura and a team of other designers working in government have led a huge piece of research and have published a blog post about their work on the GOV.UK design notes blog](https://designnotes.blog.gov.uk/2022/11/28/designing-for-people-with-dyscalculia-and-low-numeracy/).

Laura explained that while we often think of numbers as neutral, almost clinical things, they’re actually far from it.

She explained to me that for her, numbers are emotional.

She told me to think about the importance of statistics when it comes to things like COVID-19, climate change and inflation. These are things that affect all of us in a big way, and it can be really alienating if you struggle with numbers and you can’t interpret what you’re being told.

Design systems have an opportunity here to guide the way teams format numbers, and convey numerical data using things like tables and graphs.

These considerations are relatively easy to incorporate thoughtfully into our design systems, but we normally don’t, because we often don’t think about people who struggle with numbers as part of our audience - we think of them as edge cases. And it’s time to change that.

We have to start thinking first about those who our design choices are most likely to harm. It takes more time and effort to do this, but if we want to build inclusive design systems, we have to start thinking about those who are excluded, who are at the margins, and the unintended outcomes of our decisions.

3. Embrace complexity

This is a really interesting concept for me because I have very much sold my services over the years on the basis of being really good at making things simple.

In fact, if you look at the homepage of this website, you’ll notice that I reference my efforts to champion simplicity and inclusion.

This wording gives me a particular cognitive dissonance now because making the podcast has left me with a big question: Are simplicity and inclusion, in fact, incompatible?

As design system makers, we offer teams a simple way to create user experiences, by giving them reusable building blocks and guidelines to follow when they’re developing them.

But user experience is always an intersection of the products we create, and that product user’s identity, and their circumstances.

And the thing about identity and circumstances is that they are always inherently complicated.

Let’s look at an example of a common form field that many design systems offer guidance on: the gender field.

What we see over and over again are these same buckets:

- Male (male first, naturally)

- Female

- Other

And it’s that ‘other’ that I find so problematic here.

A quick count through Wikipedia’s page on gender currently reveals 101 genders. Medicine net lists 72. Another site I looked at listed 112. The exact number isn’t what’s important here.

What is important is that this does not allow any of the users who do not identify as a male or female to identify themselves correctly in our services.

And besides the fact that we actually normally don’t really need to ask this question at all, and besides the fact that asking it like this means we’re collecting data in a way that reinforces a gender binary, there is a human impact to this.

Luke Murphy, my podcast guest from episode 2, is a design advocate at Zeroheight, and is trans non-binary.

They told me that when they encounter a gender field with only male and female options, they feel “unseen”. Not a nice feeling, but a common one.

It’s very easy to think of these decisions as relatively small and inconsequential, but when you consider how many times a trans or non-binary user might encounter this pattern every day, you can quickly imagine the cumulative harm this does to a person.

And this is just one of the ways that these arbitrary choices our design systems define can scale to cause harm.

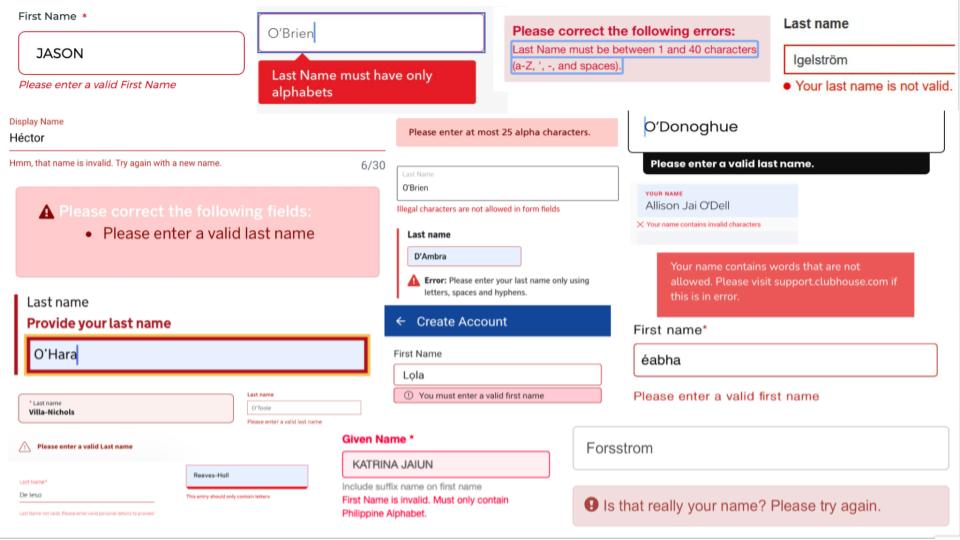

Let’s think about another one: How we ask users for their name.

Name fields are something most design systems include, but when I think about how lack of diversity in our industry as a whole really shows up in our work - this is one of the first things I think about.

Just to illustrate the scale of our bias when it comes to names, Patrick McKenzie put together a list of 40 false beliefs about names.

When these false assumptions inform our design systems, and our patterns for asking people for names, we start to exclude people.

Sheryl Cababa, my guest in the final episode of Systems of Harm, had a personal example of this.

Sheryl is an author, a lecturer and chief design officer at substantial. She’s written a book called Closing the Loop, which teaches systems thinking for designers.

She told me that her children have a double-barrelled surname, but that the two parts of their name are separated by a space, not a hyphen. And she said that there has never been a single healthcare system or service that can handle that.

Every time Sheryl or her husband engage with a service that’s stored their children’s names, they have to try inputting various permutations of the name to land on the way that the system has stored it.

And Sheryl’s experience is in no way unusual.

There are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of examples of this happening all over the internet. People are told, over and over again, that their name is not valid because it doesn’t confirm to a set of unaccommodating validation rules.

When I was collecting these examples from Twitter - I noticed a repeating comment people used over and over and over when they shared these screenshots:

This is the story of my life.

When this happens to people again and again and again, we’re giving them a clear message: this is not for you.

We become authors in that story of exclusion.

I’ve only touched on two examples here: gender and names, but the reality is that our design systems cover much more.

And when we don’t design for the full human spectrum of identities and characteristics and circumstances and experiences that our design system needs to serve, we don’t just exclude people, we erase them.

We have to be willing to engage with the full complexity of the human experience in order to build design systems that can effectively start to counter systemic harm.

We have a duty to build inclusive design systems

Thinking about how our design systems perpetuate harm is not a distraction from the work, it is the work.

Building an inclusive design system will make things harder and slow you down. There are no silver bullets here because part of building an inclusive system is reducing our speed to understand our impact.

Nothing I’ve shared today is a quick fix, but it’s a direction of travel.

It’s important that we balance the conversation around design systems and spend at least as much time talking about human impact as we do about the mechanics of our design systems.

We can choose to create inclusive design systems that put people at their heart. Even if it slows us down, we must do it anyway.