This blog post is based on a talk I did at Converge Manchester 2023 - I will add a link to the talk when it's ready. In the meantime, you may want to check out Lauren Loprete's fantastic talk on design systems and burnout from Clarity, which is part of what inspired this one.

A few weeks ago at Smashing Conf, I saw a designer called Christine Vallaure give a talk about responsive design. In the talk, she introduced a German concept that I’d never heard before: “Sysiphusarbeit” - meaning “the work of Sysiphus”.

Now if you’re not familiar with the story of Sysiphus, I’ll explain. In Greek mythology, Sysiphus was a king who was punished in the afterlife for his deceitfulness. His eternal punishment was to roll a large boulder up a hill, only to have it roll back down every time he reached the top. This task was repetitive and futile, a never-ending and ultimately meaningless effort.

And let me tell you, when I heard Christine explain this, my head snapped up so fast I almost got whiplash. Sysiphusarbeit, I realised, as I sat there in that conference hall surrounded by 300 Germans, was the best description I’d ever heard of a career in design systems.

Now, I’ll admit that I am currently giving this talk to you from the depths of burnout. It’s been a pretty trying year for reasons I won’t go into here, but it’s not the first time I’ve had these thoughts about design systems work.

In the past, I’ve likened those of us working on design systems to salmon: swimming upstream against a powerful current of opposing forces that seem determined to drag us back towards our start point.

I know I’m not the only one who feels this way. When I talk to friends and colleagues working on design systems, I hear one reflection over and over again: This shit is exhausting.

And recently I’ve started to reflect on why this is. What is it about design systems work in particular that leaves so many of us feeling burnt out? Is it the context we’re working in? Is it the nature of the work? Or is it something inherent in those of us who find ourselves innately drawn to roles that demand systems thinking?

And more importantly, is there anything we can do about it? Because the bottom line is, as much as I feel exhausted by it, I actually like this work. Even though it frustrates me and exhausts me, there’s a reason I keep doing it beyond being a glutton for punishment. I just wish it was easier. And I think that’s probably true for a lot of us.

So in this post, I’m going to share some reflections about design systems and burnout, and some ideas about what might make things better.

What is burnout?

I want to start off with a definition of burnout to make sure we’re all on the same page.

The technical term was first coined by a psychologist called Herbert Freudenberger in 1975. It was characterised by 3 components:

- Emotional exhaustion - the fatigue that comes from caring too much, for too long

- Depersonalization - the depletion of empathy, caring and compassion

- Decreased sense of accomplishment - an unconquerable sense of futility: feeling that nothing you do makes any difference

And when it comes to design systems, I think it’s the third component that most commonly leads us to burnout.

Why do design systems cause burnout?

Broadly speaking, I think there are 5 reasons design systems can contribute to a decreased sense of accomplishment, leading to burnout.

They are that:

- We value outputs over outcomes

- Design systems are seen as static products, not living services

- Design system value is hard to quantify

- We hear more about our failures than our successes

- Our lens is too wide

So let’s look at each of those in more detail, starting with the first.

1. We overvalue outputs over outcomes

As we’ve started to converge on a definition of design system, we’ve started to treat them like a checklist of things to deliver.

I see an overemphasis on artefacts and deliverables: things you can point at, at the expense of what they really are: large scale organisational change programmes.

One common way I see this manifesting is in a phenomenon I see in design system teams over and over. Something I like to call: the post-launch crash.

Pre-launch design systems teams are typically galvanised toward a shared and specific aim: launch the design system.

During this phase, the team has its collective eyes on a collective prize, and any and all work, discussions, disagreements, stressors and detours happen in the warm glow of a very bright light at the end of the tunnel.

However hard things are now, we think, it will all be worth it in the end.

I’ve lived through this myself.

Here’s a picture of me and the team at GDS the day we launched the GOV.UK Design System.

I’m not exaggerating when I say this was probably the best day of my career. 18 months of research, design, redesign, documenting, testing, iterating, and failing and eventually passing our funding review, all came to fruition on this day. The relief was palpable and only surpassed by the pride I felt at what we’d managed to achieve.

Twitter went off. Design and tech heroes of mine were sharing our work and praising the thing we’d created. Any exhaustion I felt in that moment was swept away in a flurry of excitement, and recognition and glory. It was, indeed, all worth it in the end.

But here’s the thing: what I know now, what’s so obvious with hindsight, is that this wasn’t the end. It was only the beginning. The beginning of something that I now know is endless, and relentless, and hard.

That light at the end of the tunnel turned out to be nothing more than the entrance to another, and for many design system teams, it’s the only one they ever get.

Giddy from the euphoric moment of going live, bolstered by a sea of congratulations and accolades, design system teams breeze confidently into post-launch land, ready to bask in the glory of their efforts, as teams begin to adopt the system and incorporate it into their day-to-day work.

But it’s at this point, as teams start to kick the proverbial tires of what we’ve done and stakeholders start to ask “what’s next?”, that we often come to realise that the people in our organisation have fundamentally misunderstood the nature of what we’re offering.

Demand surges, we are bombarded with reports of the gaps in our system, and stakeholders start to question whether our team even needs to exist anymore, now that we’ve delivered the product they were expecting.

And this links to the second reason that design systems cause burnout.

2. Design systems are seen as static products, not living services

While awareness of design systems has matured significantly over the past decade or so, a continued sticking point seems to be around organisations understanding the need for ongoing investment.

This is absolutely not helped by external agencies and consultants - and I do my very best not to be one of them - who promise to “come in and build you a design system”.

As an aside, if you are a consultant or you work for an agency who does this, please, on behalf of in-house teams across the land - stop.

It’s like promising to build a national rail service, without giving thought to who’s going to drive the trains once the tracks are in place.

Design systems are a service that come with ongoing operational costs, but the idea that design systems are single-point deliverables is a pervasive myth that won’t die.

And while I know I’m preaching to the converted here, I think there are 2 aspects to this that contribute to burnout.

The first is that product teams using the design system will often place unrealistic demands on a design system team to provide everything that they need from day one.

As design system makers and maintainers, we know that our systems will grow and evolve over time. The gap between what teams need and what we’re able to offer will shrink as the system matures - that rather than solving every need from day one, our task is to reduce duplication of effort as time goes on.

But to people who’ve never worked on a design system, this isn’t always as obvious as it is to us. Rather than viewing the design system as a living entity with ever increasing returns, they focus on the gaps. This leaves us facing a firehose of demand that can make us feel as though nothing we’re doing is ever enough. I’m going to talk about that more in a few minutes.

The second problem this misconception causes is that it can create a threat to our funding. Stakeholders who misunderstand the evolutionary nature of design systems can assume that once we’ve shipped version 1, we’re no longer needed.

Budget holders who don’t understand the need for us to provide ongoing support, to add to and update the system, and to run processes like contribution are quick to assume they can reallocate our time to work they consider pressing.

No matter how many times we explain how things really work, this misunderstanding seems persistent, and it leaves us in the position of constantly having to defend ourselves, and prove our worth.

The constant need to explain why what we’re doing is valuable is exhausting, and really feeds into that feeling of futility - that nothing we do is ever enough.

It’s also really challenging.

3. Design system value is hard to quantify

Even in organisations with the most supportive leadership, it’s not enough to just say “trust us, we are delivering value”. Eventually, someone is going to say: Prove it.

And despite a wealth of literature, conference talks, panel discussions and relentless discussion on how to effectively measure the impact of design systems, most of us still find this inherently hard to do.

I think there’s a few reasons for this.

For starters, while it’s much easier to gather qualitative feedback on the value of our design systems - like glowing testimonials and anecdotal benefits from people who like the design system - it’s often not really what the business wants from us.

Because, what that stakeholder really means when they say “prove it”, is “Prove it with numbers”. “If it’s money you want, then give me something I can attach a clear cost to.”

When it comes to gathering quantitative data, there are 2 areas we can look at, and both are problematic.

The first is to look at our impact on the products the design system is used to create:

- Have we helped to increase conversion?

- Has our customer satisfaction score improved?

- Has engagement gone up?

- Are product updates happening more often now?

This presents a real challenge for design system teams, because our impact on the end-user experience is always diluted and mixed in with other factors, like:

- product teams’ delivery processes

- the efficacy of other systems and resources teams uses

- the health of design and developer operations in the organisation

Pin-pointing - to any degree of accuracy - a design system’s impact on quantitative product metrics is an unwinnable game, but is often one we’re asked to play anyway.

Our second option is to look at metadata about the design system itself. Things like:

- the number of teams adopting the design system

- number of components used

- % of products built using the design system

While these things are definitely easier to measure, they are only meaningful if our stakeholders fundamentally believe in the value of the system already. Nobody wants the whole company to be using something they don’t see the point in.

This is not an easy problem to solve. To my knowledge, no one has found a universal formula for persuading stakeholders to keep the money coming in.

The best we can do is understand what our organisation cares about, and build up a picture that taps into that. But it’s not much fun is it?

Making the case for continued funding is difficult, tiresome, and probably not why most of us got into this work - but it’s inescapable.

I think this is worth acknowledging because it all contributes again to this decreased sense of accomplishment.

This can make it feel like we’re speaking a different language to our stakeholders and users. We might know that what we’re doing is helping. We might know that we’re working as hard as we can. But if we can’t tell that story in the way people want to hear it, we’re told it isn’t good enough.

4. We hear more about our failures than our success

I often hear people describing design systems work as thankless, and I definitely understand where that comes from.

As design system maintainers, we are providing a service to the organisation. And, as with any service, people are way more likely to tell us when we’re getting it wrong, than when we’re getting it right.

This is completely normal, but it somehow feels more personal when the customers you’re serving are also your colleagues. I think that subconsciously we expect that fellow designers and developers would take the time out to give us good feedback. The fact that they know, on some level, what it’s like to do our jobs, makes their silence on our successes feel inhumane.

But here’s where I’m going to say something a bit strange.

You know how they say “No news is good news”? If we apply this to design systems, we can assume that no feedback means everything is working as expected and our users are satisfied?

Well I also think, in the case of design systems, that bad news is also good news.

Since the vast majority of design systems are not mandated, that means we’re reliant on teams in the organisation choosing to use them, over alternatives like creating their own product-level solutions, or in the worst-cases, setting up their own design systems.

So when teams take the time to tell us that:

- “This header component only has space for 4 nav items but we have 5”

- “Your focus state doesn’t work properly in Safari”

- “I tried to contribute a pattern but no one has come back to me”

- “We use a different theme on this part of the site and your tokens don’t support it”

I see it as a sign that they’re engaged and, on some level, invested in its success. Or at least, rationally, I do that.

But however our logical brains might process this as a positive indication, we are not robots. We are human beings, doing our best, and this doesn’t feel nice, and it creates an unfortunate paradox.

As engagement, buy-in and usage of the system increases, so too does the amount of criticism - constructive or otherwise - we receive. That means that the more impactful our design system is, the more we’re going to hear about its shortcomings.

Our success is going to make us feel like we’re failing, by design.

As well as being kind of demoralising, it also makes it really hard to prioritise. When goodwill and trust is our currency for encouraging adoption, it makes it really hard to put these issues on ice.

And this leads me into the fifth and final reason that I think design systems cause burnout.

5. We care too much about too much

As systems thinkers, we are hard-wired to keep our eye on the big picture, and all of the problems it contains.

This creates a couple of issues that can significantly erode our sense of progress.

Firstly, we understand that our design systems are made up of lots of interconnected parts, and that even seemingly small decisions we make could have consequences for its overall health.

We know that design systems are multipliers. A single design choice that we make can quickly get scaled across multiple products, affecting hundreds, thousands, or even millions of product users.

And if we get it wrong, then rolling back on that choice creates widespread disruption to adopting teams.

In my experience, this tends to make us cautious and fairly risk-averse, meaning we often want to take our time to build confidence in our decisions before making updates.

And that’s not a bad thing. To a degree, design systems teams need to move at a slower speed than product teams, because of the scope and scale of their work.

But it can go too far. I’ve worked in teams where we’ve as good as ground to a halt for fear of making a misstep. When we see every move as having the potential to cause far-reaching disaster, we stop making progress.

Secondly, being aware of all the problems means being aware of all the problems you’re not solving.

The breadth of the work we’re doing means there’s pretty much an endless supply of issues to fix and improvements to make.

And I do think that as systems thinkers we are especially empathetic, and especially sensitive to the pain of saying no, even though we know it’s necessary.

Even if we know we cannot be everything to everyone, I think that we’re kind of hard-wired to want to.

In fact, I’d say it’s the very qualities that make us good at our jobs - our empathy, our problem-solving skills, and our ability to hold the whole picture in mind - that make us so vulnerable to burnout.

And in the same vein, I think that the reasons we’re drawn to this work in the first place - the desire to help people, to have an impact, to make a difference - that can end up driving us out of it.

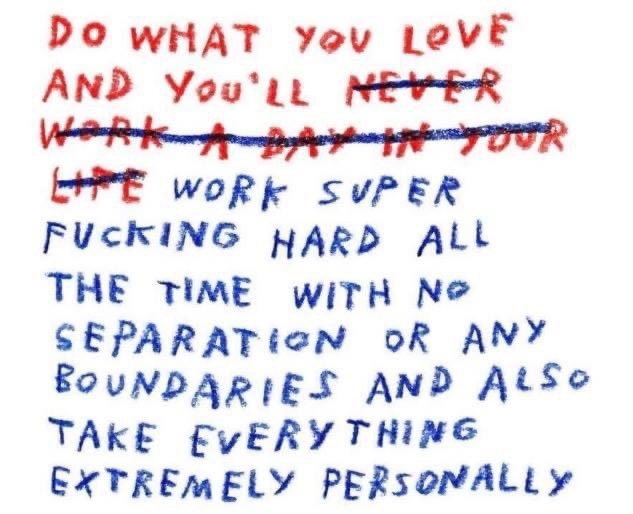

It makes me think of this meme created by Adam JK:

So. On that cheery note, let’s talk about what to do…

Can we put the fire out?

So is there anything to be done, or should we all just quit right now?

Well, you could quit.

I want to validate that it’s OK to walk away from this work, for a time or forever. Design systems, contrary to how we sometimes feel about them, are not life. You existed before you worked on design systems and you will continue to exist after them.

With all of that said, for many of us, the benefits of this work will still outweigh its drawbacks.

So, if we do decide to stay, how can we better protect ourselves about burnout?

At the start of this post I said that I thought the key to design systems burnout lay in that third component defined by Freudenberger, that it was rooted in this decreased sense of accomplishment?

Given that, I think this is also where the solutions lie.

To protect against burnout, we have to cultivate a sense of accomplishment

To really counter the risk of burnout, we have to cultivate a sense of accomplishment.

So how do we do that?

I have a few suggestions. 4, to be exact.

1. Tell a better story

The first is that we have to start telling better, more accurate stories about design systems and what they offer.

This is especially important at the pitching stage, when we’re waxing lyrical about how much money our systems will save the business when we’re no longer throwing the company’s money down the drain rebuilding buttons.

We need to make it super clear that design systems won’t eradicate duplication of effort, but that they will gradually reduce duplicated effort over time so long as the business continues to invest in them.

We need to over-communicate about the realities of this work with our users and our stakeholders, to take pressure of that launch moment and to convey that design systems are a continuous practice, not a set of artefacts to deliver.

This might be a harder sell than an over-simplified sales pitch that says design systems will save 25% of a company’s design and development costs, but it will put us in a much better position to show off the value we do deliver.

2. Radically descope

We have to accept that we cannot be everything to everyone, and setting overly-ambitious goals is only going to contribute to a feeling of failure.

How much we have capacity to concentrate on at any one time depends heavily on the size of our team and the maturity of our design system, but when goal-setting, it’s a good idea to think about:

- which users we most need to support

- which products we most need to serve

- which platforms we most need to accommodate

- what we can’t commit to

And if I’ve learned one thing in the past 7 years working in this space, it’s that it’s always less than you think.

Setting achievable goals means you actually get to feel a sense of achievement, rather than thinking about all the things you didn’t manage to do.

3. Celebrate success often

We can all help to cultivate a culture of appreciation within our teams by acknowledging each other’s wins and calling out good work.

It’s an oldie but a goodie, but making sure there’s always space in team retros to talk about what went well is so important. And when you’re in a retro, contribute to this.

It’s so easy to go into the room with a list of things you want to improve, but it’s equally important to acknowledge what you’re getting right.

And I’m a big fan of the rule, whenever you ship something: cake. Here’s an example of a showstopper I made for the GOV.UK Design System when we shipped a set of accessibility changes on our 1 year launch anniversary.

This might seem frivolous, but it really does pay to take the time to mark your successes, and to look in the rear view mirror from time to time and say “yeah, we did a good job”.

And don’t just keep it to yourself. Spam Slack with your design system updates. Do a weekly round-up of everything you’ve done that week. Bask in the dopamine hits as people react with emojis and a torrent of cut and pasted “well done”s.

It may all sound like I’m being a little flippant here, but celebrating success reminds us to have fun in our work, and I’ve found that its effect is cumulative. The more you get into the habit of reminding yourself that you’re doing a good job, the more you’ll start to realise that you are.

4. Reconnect to your purpose

Design systems have taken on a life of their own. Once a means to an end, they have become the end itself. Organisations no longer talk in general terms about wanting to improve efficiency or make their products more consistent, they simply say “we need a design system”.

But design systems are not one thing and - no matter how many consultants like me might try to sell you an out-of-the-box approach - there’s no template solution.

Approaching design systems in a formulaic way leaves us with a checklist of artefacts to deliver, and means we lose sight of our purpose.

But to really feel that sense of accomplishment that’s so important for counteracting burnout, we need to reconnect to our specific why, both on a personal level and a team level.

Individually, why did you start working in this space in the first place? What itches did it let you scratch? Personally, I care about creating more inclusive experiences and helping people to connect with each other, and design systems are my current best way of doing that. When I feel burnt out, reminding myself of the decisions I’ve made and the work I’ve done to this end, along the way, helps me to realise that I am making a difference.

And what motivates you and your colleagues as a collective? What gets you all fired up? What kind of work gives you meaning? What unites you as a team and gives you shared meaning?

And this is key.

I believe that design systems work is really effective when it comes to helping us to feel part of something bigger than ourselves. The reach we have weighs heavy sometimes, but it also helps us to see the things that connect us.

Know you’re not alone

Burnout is a hard place to be, and if you’re working on design systems, then the unfortunate truth is that the career path you’ve chosen and the type of person you are means you’re probably at a greater risk of burning out than the average.

But one thing you are not, is alone in that.

We are in this together, and I know that when I’m struggling with burnout, a huge part of what pulls me back out of it is the community around me.

As systems thinkers, I believe that we are intrinsically smart, capable, empathetic and compassionate people, and our community is one of the strongest tools in our arsenal.

We are collectively a force to be reckoned with.

You’ve got this, and we’ve got you.