This article is based on a talk I delivered at Converge London 2022 - here's the video in case you'd prefer to watch it.

“It’s foolish to think a [design system team] sees everything, let alone understands all the subtle forces at play across an experience. It’s product designers and developers on the front lines, working to solve customer problems on a daily basis, that bring that seasoned perspective.

"The practice of contributions injects a much wider representation into the features and tools the system offers. Contributions bring new ideas, extending what a system team hasn’t seen or considered. Different patterns come into play, test and expand the work.”

I agree with this unequivocally.

In my 6 years working on design systems, I have rooted for fostering a sustained contribution practice in every organisation I’ve worked for and with.

But most of us working on design systems find it hard to achieve. I’ve struggled with this in my own work, and I know I’m not alone.

I regularly speak with organisations who tell me:

- “We’re struggling to get people to contribute”

- “People aren’t following our contribution guidelines”

- “The things people contribute are a long way off being ready to release”

There’s a sense of swimming against the current. No matter how hard we try to achieve a steady flow of contribution, it seems like not contributing is the natural default.

Even teams who have fostered a sustained contribution practice tell me that the effort to reward ratio seems, somehow, off: That the time and effort required to elicit regular contribution, of a releasable standard, leaves them questioning if it’s worth it.

To explore why that is and what we can do about it, I’m going to invite you down a path of politics and economics. And more specifically: Capitalism and socialism.

A whistle stop explanation of capitalism and socialism

Capitalism is a system in which the means of production are privately owned.

The function of a capitalist system—and all of its constituent parts and processes—is to help private owners make as much profit as possible. They are free to grow their wealth and resources without regulation or interference from the government.

Critics of capitalism say that it disproportionately benefits a wealthy few, creating stratification of social classes and reinforcing systemic inequality.

In a socialist system, the means of production are publicly owned by everyone.

The purpose of a socialist is to distribute wealth and resources equally across a society.

Critics of socialism say that it removes the incentive to compete and so leads to a lack of economic growth.

What does capitalism have to do with design systems?

Since we live in a capitalist society, we can think about our organisations as a microcosm of that society.

We are incentivised to help our organisation’s owners and shareholders to make a profit.

More often than not, we are incentivised with the promise of power.

For individuals within the organisation, power translates to:

- influence

- career progression

- visibility, either inside or outside the organisation, or both

- immunity from consequences of disobedience and poor performance

For teams, it usually means::

- influence

- product performance (usually in the form of profit or money saved)

- visibility, either inside or outside the organisation, or both

- immunity from consequences of poor performance

How design system teams earn power

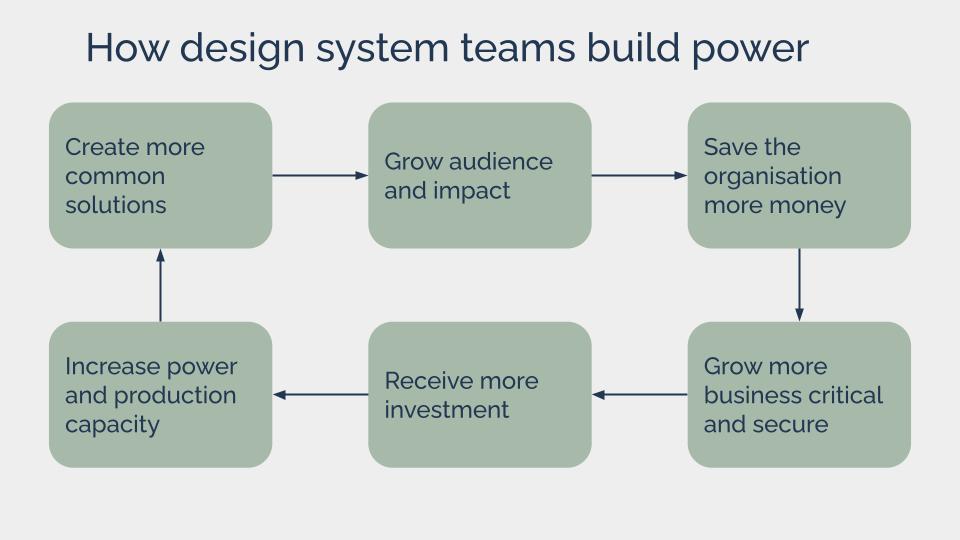

Design system teams can build power by creating common solutions that help other teams in the organisation to work more efficiently.

The more of these common solutions they're able to produce, the larger their audience grows and the more impact they have, the more money they save the organisation, the more business critical they become, the more investment they receive and, ultimately, the more power and production capacity they have.

And this becomes self-reinforcing as they can then use that extra capacity to create more of that common infrastructure that the organisation values and grows to depend on. And the cycle continues.

So where does contribution fit in?

Contribution to design systems is a socialist ideal

The idea of opening design systems up for contribution from other teams in the organisation is usually described in socialist terms.

It says that if everyone contributes to a design system, the design system becomes better for everyone in turn.

Capitalism discourages contribution by design

People are not incentivised to contribute

In a capitalist environment, a person's ability and motivation to contribute (or not) is governed by the best chance of earning power.

And most people earn more power from their core role than they do from contributing to a design system.

Design system contribution is usually not part of a designer or developer’s job description.

Even when it is, contribution takes time away from a person’s day-to-day work, which is normally what people are assessed against and compensated for.

So design system teams can spend time trying to elicit contribution, but they'll be working against the organisation’s default incentive framework.

Design system teams are not incentivised to support contribution

Spending too much time trying to elicit contribution threatens the design system team’s own power.

The more time they spend driving contribution, the less time they can spend producing that common infrastructure that they need to earn power.

There is sometimes a belief that contribution can help design systems grow faster. That by getting more hands on deck, the team can deliver more work, more quickly.

But as anyone who’s implemented a contribution practice will tell you, it’s not the reality.

When Nathan Curtis interviewed a group of design system leads in 2020, they told him that although contribution was valuable for other reasons, they “do not reduce workload and do not make [a] system produce more”.

In fact, in my experience, contributions actually increase workload and make our systems produce less.

Supporting people to contribute, and to produce features and documentation of a releasable standard takes longer than it would for a design system team to do the work themselves.

This means that most design system teams earn more power by building their system, than they do by helping people to contribute to it.

Even if you care about contribution, the system will work against you

Now I want to stress that I’m talking about systemic incentivisation here, not individual motivation.

You, as an individual, might be highly motivated by the idea of contribution, and investing in a greater good.

And if you’re working in a design system team, you might be committed to the idea of making contribution a success. You might even be willing to relinquish power to achieve this.

But the fact is that the system we’re operating in is not built to cultivate this.

So it’s not too far of a stretch to say that contribution, in this environment, is destined to fail.

But there's another layer of complexity that makes this even more problematic.

How contribution models can reinforce inequality

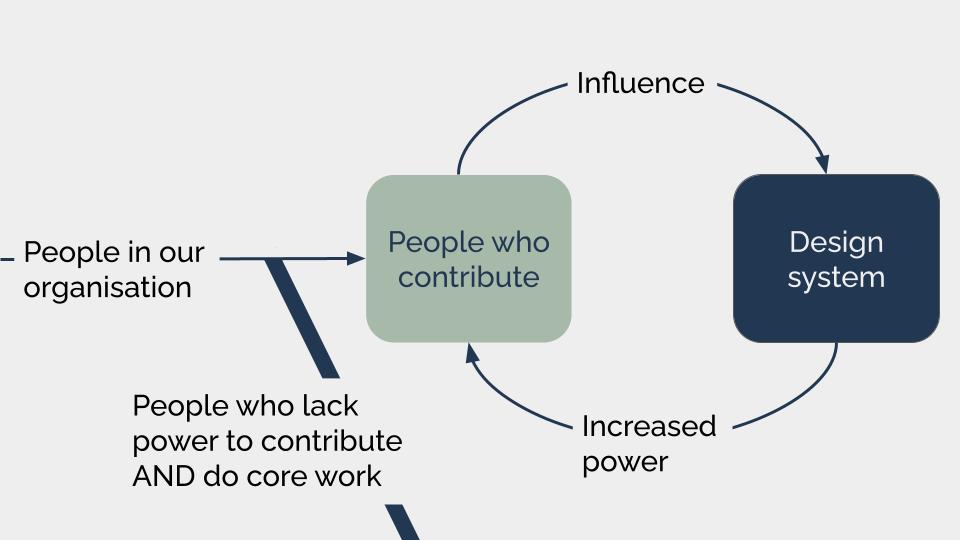

Earlier on I said that most people earn more power from their core role than they do from contributing to a design system.

While that’s true for most people, a small number of people get to both.

And that’s because even though we are all incentivised to earn power, some people already have it.

Now that might be because they earned it. They might have worked their way to the top and earned that influence that they have, and that visibility, and a degree of immunity from consequences.

But often, power comes from privilege.

Our systems do habitually favour some people and they do disadvantage others - whether that’s because of race, gender, religion, socio-economic background, disability, or any other number of things that impact the amount of power people have.

That’s why some people in our organisation are free to earn power through contribution and their core role, while others have to choose.

People who already have power don’t need to earn it as much, so they can afford to take time out of their core role to contribute to a design system.

They are influential, visible, and trusted already, and so they have less to lose than those without power.

And this inequality becomes self-reinforcing. If only individuals who have enough power already are able to contribute, then only those individuals can increase their power through contribution.

Over time, this widens the gap between those with power and those without.

And this doesn’t just affect the people in our organisations, but also the people who use our products. Because we’ve got to ask ourselves if it’s really possible to create a design system that represents a broad set of needs and perspectives, if only a privileged few can help shape it.

Viewed through this lens, contribution as a socialist ideal is not merely doomed not to work: it’s actually destined to reinforce inequality.

Can we make contribution viable and more equitable?

The capitalist system in which we’re operating is designed to impede a fair and representative contribution practice. Armed with this information, it seems as though we can either:

- Revolt: change the system in which we’re operating so that we can realise our socialist aspirations

- Give up: Accept the system in which we’re operating, forget about contribution altogether, and have the design system team make everything

To most of us, this choice probably feels a bit disempowering.

Spearheading a full-blown revolution probably feels, at best, a bit daunting to most of us. And, in any case, there are probably better contexts in which to discuss that than in an article about design system contribution.

And forgetting about contribution altogether doesn’t seem optimal for most of us either.

Uphill battle or not, there’s a reason so many of us persist at trying to establish a contribution practice.

It’s hard to imagine a context in which a completely autocratic design system team could succeed. Most designers and developers expect a degree of input into the decisions a design system encodes, and would struggle to trust one they couldn’t influence.

What’s more, regardless of whether or not design system contribution is compatible with a capitalist environment, most of us agree that its purpose matters. Representation matters. So we’re probably going to keep trying, despite a low likelihood of achieving that goal, given the way we currently approach it.

So instead of considering this a binary choice, let’s think of it as a spectrum. What opportunities lie in the middle ground between these two responses?

And instead of getting caught up in wondering whether we as individuals have the power to change things, let’s try asking a more empowering question:

“What can I do from where I sit?”

This question was introduced to me by coach and author Sara Wachter-Boettcher - and it’s a great way to break free of this kind of disempowering, binary thinking.

This is a complex, systemic problem with a myriad of imperfect, overlapping solutions to explore - so I don’t have a concrete answer to this question.

But I do have some thoughts that I hope might form the beginning of a conversation.

1. Recognise and name the problem

I think there is immense value in naming this problem - if only to provide reasoning and validation for the creeping sense of burnout many design system teams experience when negotiating this challenge.

If what I’ve talked about here resonates, then I encourage you to spend a bit of time with it.

How does it feel to consider that it’s not you getting it wrong, but rather that the task you’re faced with, and the capitalist system you’re working in, are in conflict with one another? What might we do differently?

Recognise that this is not just your problem to own. This is a systemic issue.

Naming and agreeing on the nature of the challenge we’re facing is the first step towards figuring out where we go next.

2. If we want to build representative design systems, contribution models must redistribute power

To be more equitable, our contribution practice must rebalance power between the people who can contribute, and those who can’t.

How can we empower a more diverse group of people to contribute?

Can we make it so that everyone receives a comparable return on investment for contributing?

Can we remove barriers, to lower the amount of time and effort involved for those who struggle to contribute? And can we introduce better incentives to increase the power they’ll derive from it if they do?

To be able to answer these questions, we have to know what bargaining chips we have to offer.

In other words, we have to identify our organisational currency.

3. If power is capital, what’s our currency?

If power is the main incentive in our organisations, then we can think of currency as the systems that teams and individuals can use to trade power.

Currency can be something that’s officially recognised.

For example, exceeding the objectives set out in your performance framework is a form of currency. Your performance over the course of a year surpasses what was expected of you, your line manager records this, and you receive power in the form of a bonus or a pay rise. In theory, at least.

Currency can also be unofficial.

Being friends with your boss might be a form of currency. The organisation makes a round of redundancies, and they put in a request for you to be kept safe. Your power is derived from that relationship and results in job security. This kind of currency might even be denounced by your organisation at an official level, but that doesn’t make it less real, or indeed, less valuable.

Organisational currency can range from getting a shout out in the monthly all-hands for a piece of work well done, all the way through to a promotion to director level.

Once we start to understand the systems of currency our organisation uses to buy and sell power, we have something to barter with. We understand how to participate in those systems, and when and how to disrupt them.

4. Balance acceptance with activism

The appropriate balance between acceptance and activism will depend on your organisation’s structure and culture.

However, in general I identify 3 main options for reconciling the socialist practice of contribution with the capitalist system we’re in.

- Change our organisation’s culture and power structures to support contribution - this is the most radical and disruptive opinion.

- Update our system(s) to make more space for contribution

- Work with our system(s), designing our contribution practice around it.

For example, in strictly-governed organisations where people don’t get to choose what they work on, spending our time touting the value of contribution to designers and developers is going to be of limited value. They might care, but the system is designed to prevent the majority of them from being able to act on it.

At the most extreme end, we could aim to create a fundamental shift in the organisation’s culture to support a more autonomous way of working.

If that isn’t possible, we may work with the discipline leads and managers in our organisation to make contribution a recognised part of people’s roles, so that they’re allowed to dedicate time to it during their working hours.

And if that’s not an option either, then we can adapt our approach to be more proactive about eliciting contribution.

Rather than having contributors approach us, can we go to them? How could we harvest their insights and experiences to create a richer and more representative design system, without putting the onus on proactive contributors? We still need to think about what we can offer in return, but we can shift the deal in their favour if we reduce the investment required.

I believe that we can work to make contribution viable and more equitable, but this is a long game and there are no quick fixes.

In conclusion

Working on a design system can feel like an exhausting uphill battle at times, and I hope I’ve helped to shed some light on why that is.

I’ve spent the past 6 years working in this space, and I’m often struck with a sense of attempting an impossible task. No matter how hard we work to foster these socialist ideals, like community, collaboration, and contribution, it feels as though we’re always being dragged to a default culture of individualism.

But rather than continuing to swim upstream, stopping only now and then to complain about how hard it is, we can turn our attention to the current.

We can start to explore the forces that are working against us and ask ourselves why those norms exist and persist. It’s not because we’re doing a bad job - it’s because contribution is a socialist ideal that’s hard to establish and sustain in a capitalist system.

And none of that means we shouldn’t try.

We should try, and keep trying, because fair and equal contribution means representation. We aspire to it because it matters: representation matters, and so contribution matters.

So let’s face those challenges head on. Let’s see and accept those capitalist systems, and work to change them where we can. Let’s find opportunities for activism and learn when to work with the cards we’ve been dealt.

The task we’ve set ourselves is impossible.

Let’s keep going.